Plant hormones help prevent bitter pit

PGRs proving to be effective bitter pit management tools.

BY Matt Milkovich

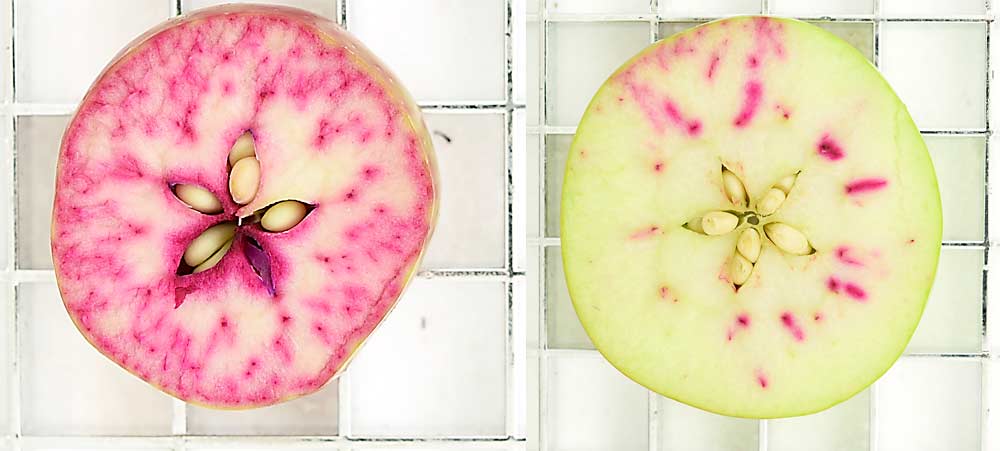

Michigan State University researchers use dye to measure apple xylem functionality, which gives a good indication of where calcium is able to travel. In the Gala (a variety not known to be susceptible to bitter pit) at left, there’s complete xylem function in both the fruit interior and near the peel. In the Honeycrisp (a variety known for its susceptibility to bitter pit) at right, only about 20 percent of the vascular structure (the xylem and phloem) in the outer cortex is still functional. Because bitter pit initiates in the outer cortex, just under the peel, it’s very important that the outer cortical vasculature remains functional.(Courtesy Chayce Griffith/Michigan State University)

Michigan State University researchers use dye to measure apple xylem functionality, which gives a good indication of where calcium is able to travel. In the Gala (a variety not known to be susceptible to bitter pit) at left, there’s complete xylem function in both the fruit interior and near the peel. In the Honeycrisp (a variety known for its susceptibility to bitter pit) at right, only about 20 percent of the vascular structure (the xylem and phloem) in the outer cortex is still functional. Because bitter pit initiates in the outer cortex, just under the peel, it’s very important that the outer cortical vasculature remains functional.(Courtesy Chayce Griffith/Michigan State University)

In order to reduce bitter pit, a calcium-related postharvest disorder in apples, you need to improve calcium delivery to the fruit. But researchers are still trying to figure out the best way to achieve that.

Auxins and abscisic acid, two classes of plant hormones, just might be the right tools. Michigan State University researchers have been applying them for two seasons, and the results so far are extremely promising.

During Honeycrisp trials at MSU’s Clarksville Research Center in 2021, the hormone applications reduced bitter pit by up to 65 percent, an “enormous reduction,” said MSU tree fruit physiologist Todd Einhorn.

They’re still working through the 2022 data, but what they’ve seen so far looks encouraging, said Chayce Griffith, Einhorn’s graduate research assistant.

In apples, calcium is transported via xylem. The xylem in the fruit breaks down naturally over the course of the season, particularly in sensitive varieties such as Honeycrisp and Jonagold. The process begins early in the fruit’s development, and by harvest there are hardly any xylem connections within the flesh of the apple, thus limiting calcium transport to the peel where it’s needed. Auxins and abscisic acid extend calcium delivery by improving xylem longevity and functionality, Einhorn said.

Related:

The MSU researchers used the commercial plant growth regulators NAA (naphthaleneacetic acid) and ABA (abscisic acid), as well as IAA, a native auxin in apples. They also tried IBA, another commercial auxin, but stopped using it because it didn’t reduce bitter pit, Einhorn said.

Griffith said IAA and ABA were especially effective in the trials. IAA proved to be very effective early in the season, a crucial period for the fruit’s calcium uptake.

NAA “sometimes shows flashes of being really useful,” but more study is needed, Griffith said.

Environmental conditions can affect plant growth regulator performance. NAA did not work well in New York trials conducted by Cornell University, Einhorn said, but it worked extremely well in two Washington state trials, virtually eliminating bitter pit in the treated trees.

In the MSU trials, the plant hormones were applied to whole tree canopies at several rates. ABA was applied at 62.5, 125 and 250 parts per million; IAA at 5, 10, 20 and 40 ppm; NAA at 2.5, 5, 10 and 20 ppm. The applications were made 30, 45 and 60 days after full bloom. The treatments were replicated five times, with several trees per replicate, Einhorn said.

Griffith said the research team will continue to experiment with the compounds, dialing in on ideal application rates and dates before making recommendations to growers. They’ll also do molecular work and nutrient analysis in the lab.

Last June, Einhorn walked Good Fruit Grower through the trial block. An auxin application had been made about a week before and was already having a “marked effect” of increasing the xylem, he said.

“This is a new approach to managing bitter pit by creating more xylem and reducing the rigidity of the xylem through auxin,” he said. “We’re improving the longevity or life of the xylem, and that may be allowing more calcium into the fruit over time.”

Transferred link:https://www.goodfruit.com/plant-hormones-help-prevent-bitter-pit/

Enhancing fruit quality

Enhancing fruit quality